Over the last few weeks, we have seen demand for credit explode as companies prepare for the viral shutdown. This has compounded to further strain a financial system that was not prepared for the Coronavirus. While the volatility and declines in prices are reminiscent of the financial crisis, it is important to understand what pressures banks are now facing and how they are a bit different than what they were facing in 2008. Looking through this noise, there are likely some opportunities, but it will require a discerning investor with an iron stomach to take advantage of them.

There are iconic images from the Great Depression of people standing in lines outside the bank, as depicted in the film “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Frantic customers demanded to withdraw their deposits out of fear. Given our electronic age, you would never see a line at the local branch today. In recent years, you rarely see customers in a bank branch, let alone a line out the door. Further, with the backstop of FDIC and the Federal Reserve, most depositors consider their funds safe.

There are iconic images from the Great Depression of people standing in lines outside the bank, as depicted in the film “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Frantic customers demanded to withdraw their deposits out of fear. Given our electronic age, you would never see a line at the local branch today. In recent years, you rarely see customers in a bank branch, let alone a line out the door. Further, with the backstop of FDIC and the Federal Reserve, most depositors consider their funds safe.

Over the last four weeks, we have seen a bit of a corporate run on the bank. There were not lines at the bank. This time, it was just a backlog of a demand for loans in the form of everything from mortgages to corporate credit. How did this run happen? Can’t a bank decide how much they want to loan? Not exactly.

Companies regularly setup credit lines so they can secure funding from banks if they need some extra cash. These credit lines are the equivalent of a Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) on a house. Consumers sometimes use a HELOC to finance a large purchase, remodel project or to just pay off more expensive credit card debt. Similarly, banks offer these credit lines as a service to their business customers in exchange for a small maintenance fee. The interest rate terms are generally not that good for the business, but the business can use the credit line as a bridge financing until they tap the bond market and issue corporate bonds.

Since the economic impact of the virus-related shutdowns started to take effect, many companies are running contingency plans and are tapping their emergency credit lines. This really accelerated on March 11th when Boeing asked their banks for the $12bln line. Boeing is clearly in an emergency. They were already stumbling from the grounding of their 737 MAX aircraft and their entire customer base is reeling from cancelled flights related to the Covid-19 decline in airline traffic. While $12bln is a large amount of money, it would not be that big of a deal in a vacuum. However, this became a catalyst for other business customers to explore similar strategies.

When news of the Boeing credit drawdown broke, it was like yelling fire in a crowded theater and other companies realized that pulling some extra cash was a good idea. Blackstone and Carlyle Group added a bit of a fuel to the fire by sending a memo to portfolio companies suggesting that they prepare for a prolonged downturn.

- The line at the bank was forming and it seemed like every company wanted to draw down the maximum allowed from their credit lines at the same time. Of course, some businesses were truly in an emergency and others simply wanted to plan for the worst-case scenario.

- Either way, the increased capital demands on banks were significant and it moved into prices.

While banks do have plenty of cash, they don’t plan for all of these emergency credit lines to be drawn at the SAME time. The historical utilization of these credit lines was very low and banks did not model to get a request from all of their corporate clients at the same time. As we know, these are unique times.

How do banks fund these loan commitments? They can use existing reserves, borrow from the Federal Reserve or sell securities. Looking at market prices and data, it is clear that they are doing all three at a rampant pace. The Fed has allowed banks to reduce capital requirements to accommodate the tidal wave of credit requests. The selling of securities drove down the prices of corporate bonds. Even treasury bonds briefly declined in prices as a massive search for cash sent prices lower.

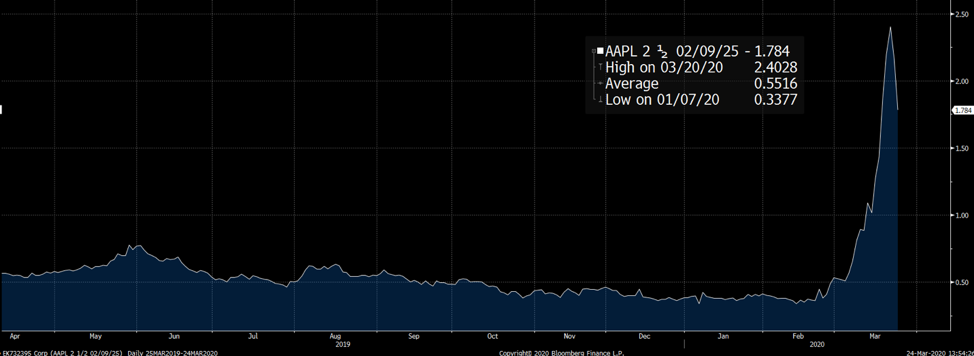

This was especially visible in the corporate bond market where we now see a significant deterioration in prices as yields have increased. Even Apple debt was priced to yield a historic spread to treasury bonds. Some banks also hold Municipal Bonds so they are also experiencing pressure as those securities are used to fund these loan commitments.

As mentioned in “Butterflies and the Tide”, the reflexive nature of markets creates a self-reinforcing feedback loop. The decline in debt prices causes ETF and mutual fund investors to question the value of their investment. This could go far beyond what is rational or maybe it is already near the limit, it is impossible to tell.

There is a glimmer of good news if one stretches to look for a light in this dark time. The discount that many large fixed income ETF’s vs their benchmarks has started to narrow with the program that the Fed announced on Monday. This could indicate that the bank run is over. However, the absolute yield on corporate bonds is generally still paltry given the uncertainty around the economy.

How does one solve this mess and stop the feedback loop? The Fed has thrown the alphabet soup of credit facilities at the issue but that is only slowing the credit run. Are banks in danger? They might not be in immediate danger as the terms of these facilities are generally pretty good at profitable spreads. There is risk that some of these loans are to a business destined to fail. However, defaults will take time to materialize.

In contrast to a 1930’s run on the bank, this is an explosion of assets versus a depletion of liabilities, so they are slower to deplete the capital base. Banks loan out multiples of their liabilities(deposits). As a banker once told me, “”Money, for banks, is crudely equivalent to inventory, for other businesses. Therefore, banks don’t generally experience cash flow challenges to the same degree as many businesses, and indeed banks are well positioned to help meet cash flow challenges. Forbearance on loan payments, even for several months is not a problem for a bank if the borrower will eventually be able to pay.” The businesses that survive this recession will likely have plenty of ability to pay as the economy will eventually function again.

Should investors buy bank stocks or invest in corporate bonds? That is not an easy call. Some banks did not adequately prepare for this worst-case scenario and some have been waiting for this opportunity to loan funds at good rates to quality borrowers. It does warrant caution on taking the playbook from the financial crisis when leverage ratios were higher and banks were loaded with toxic mortgage debt.

It is possible that the credit extended in March 2020 will turn into some bad loans. This tumultuous period will likely cause a decline in the available credit during the years ahead. Loan defaults and a decline in credit are not supportive for economic activity even if lockdowns are lifted. Some of these loans will be put to constructive use. Remember, it requires a discerning investor with an iron stomach.